TAMING THE RHYTHMS OF THE HEART

By Yoram Rudy

The Heart of all creatures is the foundation of their life, from whence all strength and vigour flows.

—William Harvey: An anatomical disputation concerning the

movement of the heart and the blood in living creatures, 1653

The last two decades have seen a dramatic improvement in the ability to diagnose, prevent, and treat life-threatening heart disease. In spite of this progress, heart disease remains the major cause of death and disability. Many cardiac disorders remain unconquered; in particular, erratic heart rhythms (cardiac arrhythmias) claim more than 400,000 lives each year in the U.S. alone, and compromise greatly the quality of life of many more individuals. The battle against cardiac arrhythmias and sudden death requires an interdisciplinary effort involving biophysicists, physiologists, biomedical engineers, cardiologists, radiologists and surgeons. Within this interdisciplinary framework, research efforts in my laboratory focus on theoretical (computational biology) approaches to the study of cardiac arrhythmias and on the development of novel diagnostic tools for these disorders. A theoretical approach to life science research has been late in coming (compared to the physical sciences) due to the complexity of living systems and the difficulty of describing the complex life processes using mathematical equations. Paradoxically, it is the complexity of the system that requires the use of mathematical models to relate observed global behaviors (e.g. irregular heart rhythms) to underlying biophysical processes at the level of cardiac cells and tissue. Mathematical models can also be used to integrate the behavior of individual system components (ion channels, single cells) to predict the global behavior of the entire system (the multicellular tissue and whole-heart); these reductionist and integrative applications of theoretical models are illustrated in Figure 1.

Heart Rhythms are Controlled by Electrical Activity

Rhythm imposes unanimity upon the divergent

—Yehudi Menuhin

The heart functions as a mechanical pump that propels blood through the circulatory system. An efficient pumping action requires a highly organized and synchronous contraction of the heart. Under normal conditions, a natural cardiac pacemaker (the sinus node) generates rhythmic electrical impulses that propagate throughout the heart as an organized electrical wave, telling it to contract. Governed by the sinus node, the heart rate is precisely controlled and the wave of electrical excitation that triggers contraction travels in a precisely defined path that is repeated during every heart beat. This organized process, however, can easily be altered by heart disease, leading to rhythm disturbances, loss of synchronization, and rapid deterioration into a state of a-synchronized contraction (fibrillation) that results in circulatory collapse and sudden death.

Why do hearts fibrillate? To answer this question, one has to understand the process of cardiac excitation at several levels of integration and of increasing complexity. The heart muscle is constructed of many individual cells that are interconnected by tubular protein structures called gap junctions. These are electrical-coupling structures that permit ions to flow from one cell to another, allowing cells to communicate electrically. The electrical impulses (called action potentials) are generated by individual cells and propagate from cell to cell through the gap junctions, forming the wave of activation that triggers contraction of the heart and synchronizes its blood pumping action. Normal electrical activity of the heart requires both, generation of normal action potentials by individual cells and regular propagation of these action potentials through the heart tissue.

Abnormal Rhythms can Begin in a Single Cell

The earth is like a single cell

— Lewis Thomas, in The Lives of a Cell

The single cell is the building block of cardiac tissue. Action potentials are generated by the flow of ions through specialized protein channels located in the cell membrane. Each channel can open and close, allowing the passage of a particular type of ion (e.g., sodium, calcium, or potassium) across the membrane between the intracellular and extracellular domains. As a rule, an inward flow of positive ions elevates the voltage across the membrane (a process called depolarization) while an outward flow of positive ions acts to reduce the membrane voltage (a process called repolarization). Following a stimulating signal (e.g., from the sinus node pacemaker), channels that conduct sodium ions open and Na+, which is present in high concentration in the extracellular domain, flows into the cell. This process causes a fast rise of the voltage across the cell membrane, generating the fast rising phase of the action potential. The sodium channels stay open for a very brief period of time, and many of them close while the fast voltage rise is still occurring. The cardiac action potential is characterized by a long plateau phase that follows the fast rising phase. The plateau is maintained mostly by the inward flow of calcium ions through specific calcium channels. Following the plateau, potassium channels open and K+ ions leave the cell, repolarizing the membrane voltage back towards its resting level and completing the sequence of events that generate the action potential.

Figure 2. The cardiac action potential and underlying ion fluxes (currents) across the cell membrane.

As mentioned earlier, the electrical action potentials trigger mechanical contraction. At the cellular level, this electro-mechanical coupling involves intracellular calcium ions that carry the contraction message to the contractile elements of the cell. The excitation-contraction coupling process involves the following steps: (1) the membrane is depolarized to generate an action potential, (2) during the action potential, calcium channels open and calcium ions enter the cell, (3) the inward flow of calcium triggers massive release of calcium ions from an intracellular storage compartment called the sarcoplasmic reticulum, SR, (4) the resulting sharp increase of intracellular calcium provides the signal for the cell to contract. Once the excitation -contraction cycle is complete, calcium stores in the SR are replenished and concentrations of Na+, K+, and Ca2+ inside and outside the cell are restored by ionic pumps and exchangers that consume metabolic energy.

The above description is a greatly simplified account of action potential generation by a cardiac cell. It serves to illustrate the complexity and highly interactive nature of the excitation process even when only a single cell is considered. Based on intuition alone, it is impossible to predict what will be the cell’s response to altered function of any one of the ion channels. Such altered function could be due to a genetic disorder, an acquired disease process, or as a result of a drug binding to the channel protein.

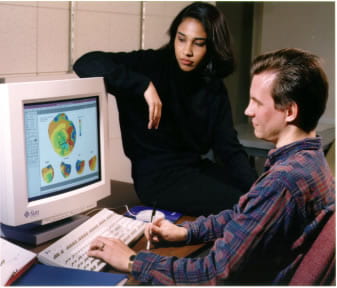

To better understand the workings of cardiac cells, and to be able to predict the cell’s electrical behavior in the presence of disease and its modification by treatment such as drug therapy, detailed mathematical models of cardiac cells were developed in our laboratory. In these models, the opening and closing of the various ion channels, the currents carried by pumps and exchangers, and dynamic changes of ionic concentrations are represented by mathematical (differential) equations. Using computers, these processes are computed simultaneously while interacting with each other and with the cellular environment, as they do in the real cardiac cell. The simulated cell generates an action potential and a calcium transient that closely resemble their experimentally measured counterparts. In other words, we created a virtual cardiac cell that mimicks the behavior of living cells in the heart.

The cell model has proven to be a most useful didactic and research tool. Sitting in front of a computer monitor, students and researchers can interactively explore the workings of cardiac cells and simulate various interventions such as the effects of antiarrhythmic drugs. As part of our arrthymia research program, we have used the model to answer many important questions regarding abnormal heart rhythms that originate from abnormal electrical activity of single cells. One example is the study of abnormal cardiac excitation associated with prolonged action potential duration. Major prolongation of action potentials could be a result of genetic mutations that modify the structure of a specific channel protein, leading to abnormal function of the channel. The hereditary long QT syndrome (LQT) is such a disorder, where genetic defects in the sodium channels or in the potassium channels delay repolarization of the action potential, causing major prolongation of its plateau. The LQT syndrome is associated with high incidence of life threatening arrhythmias and increased risk of sudden cardiac death (often during exercise or emotional stress, although in some families sudden death occurs during sleep). LQT can affect any population but is commonly observed in young, otherwise healthy people. The cell model can be used to explore the effects of channel mutation on the electrical activity of the cell. Computer simulations conducted in our laboratory provided insight into the mechanisms of arrthymias associated with action potential prolongation in the LQT syndrome. The simulations [Nature, 1999] showed that if the action potential is sufficiently prolonged by the mutation, calcium channels which normally close towards the end of the action potential, have time to reopen again and generate a second excitation wave before the action potential is complete. The second excitation phase (called Early Afterdepolarization, EAD) is generated by individual cells that could be located anywhere in the heart and at any time during the cardiac cycle. Therefore, this triggered wave of excitation does not follow the highly organized and synchronized excitation sequence that normally originates in the sinus node. The result is a loss of synchronization and the development of arrhythmias that could deteriorate to fibrillation and sudden cardiac death.

Impaired Communication can Cause Action Potentials to go Around and Around in Circles

A system is a structure of interacting, intercommunicating components

—Lewis Thomas, in The Medusa and the Snail

In the heart, cells do not operate in isolation but communicate electrically through gap junctions. Under normal conditions, in the absence of disease, neighboring cells are tightly coupled and the action potential propagates smoothly from cell to cell. If, however, coupling between cells is reduced, propagation becomes slow and discontinuous due to long delays in crossing from one cell to another through the gap junctions. Many abnormal conditions can cause partial or complete uncoupling of cardiac cells. A common clinical condition is oxygen deprivation due to reduced blood flow as a result of partial or complete occlusion of coronary arteries. The oxygen-deprived region becomes electrically abnormal (an arrhythmogenic substrate) due to both, abnormal cellular behavior and reduced gap-junction coupling.

Theoretical models of action potential propagation in the multicellular cardiac tissue were developed in our laboratory. The models represent the biophysical properties of cardiac cells and of gap junctions, and can simulate action potential propagation under various conditions of abnormal cellular function and reduced gap-junction coupling. The computer simulations have taught us that, contrary to traditional thinking, reduced coupling between cells can be as important to the development of arrhythmias as abnormal activity of the cells themselves. In fact, under conditions of highly reduced coupling, extremely slow action-potential propagation (1/20 to 1/30 the normal velocity) is observed. With such slow conduction, the propagating action potential can circulate in a small closed trajectory, called a reentry loop, that functions as an oscillator-pacemaker and drives the rest of the heart, taking control away from the sinus node. Reentry loops can develop in several regions of the heart simultaneously, causing desynchronized independent excitation of each region, fibrillation, and complete loss of cardiac function. Recent simulations produced surprising results regarding the ion-channel basis of extremely slow conduction due to gap-junction uncoupling. Under such conditions, the calcium current through the cell-membrane becomes the major current that supports propagation of the action potential [Circulation Research, 1997]. This finding is also contrary to traditional thinking that associates action-potential generation and propagation with the transmembrane sodium current.

The above examples illustrate how mathematical models can be used in the clinical context. The simulations identify reduced gap-junction coupling as a major cause of slow conduction and reentry-type arrhythmias. This observation suggests that gap junctions constitute a primary target for therapeutic interventions (antiarrhythmic drug treatment, genetic modification) aimed to improve and restore intercellular coupling. Similarly, calcium channels are identified as a target for intervention in arrhythmias that involve gap-junction uncoupling and long conduction delays. In this way, computer models can be used to identify targets, guide the design of specific drugs (or genetic modifications) for the identified targets, and simulate the effects of the intervention on a particular type of arrthythmia. I see this “computer-aided therapy” as an exciting future application of mathematical models.

New Diagnostic Tools – Electrocardiographic Imaging (ECGI)

An image can replace a word in a proposition

— René Magritte

Despite the fact that cardiac arrhythmias continue to be a leading cause of death and disability, a true imaging modality for cardiac electrical function has not yet been developed for clinical use. The readers are undoubtedly familiar with noninvasive imaging modalities such as CT or MRI. These methods are designed to reconstruct the geometrical shape and location of internal organs (e.g., the heart, a brain tumor) without the need for physical penetration into the body using catheters or surgical procedures. They can also be used to provide information, also noninvasively, about a particular function of an internal organ such as regional blood perfusion or metabolic activity. For example, MRI can be used to image a region of impaired blood perfusion in the brain, such as occurs during stroke. As stated above, a similar functional imaging modality for the electrical activity of the heart does not yet exist in clinical practice. The development of such a tool has been a major thrust of the research conducted in our laboratory.

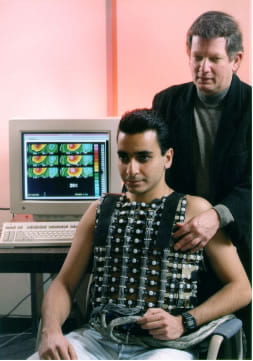

The existing method for noninvasive diagnosis of cardiac rhythm disorders is the traditional electrocardiogram (ECG). ECG measures electrical signals from six to twelve electrodes placed on the surface of the chest. These signals reflect the electrical excitation of the heart as seen from remote observation points, located on the body surface. Traditional ECG is very limited in resolution since it samples the entire body surface electric potential at only six or twelve points, leaving out very important information. Completing the missing data is analogous to completing a puzzle of several hundred pieces when only six or twelve pieces are available. Advances in electronics and computers have made it possible to cover the torso with hundreds of electrodes to obtain the total body surface ECG. This approach is known as body surface potential mapping (BSPM). Currently, we use 250 body-surface electrodes embedded in a vest that facilitates rapid and convenient application.

BSPM provides the complete set of ECG data on the body surface. From this remote information, the cardiologist has to infer the electrical activity in the heart and to arrive at a decision regarding diagnosis and treatment. Borrowing from the language of mathematics, the cardiologist attempts to mentally solve an “inverse problem”, extrapolating back into the heart from information measured on the body surface. Such a process is difficult, involves a fair amount of “guesswork” and subjective judgment, and is prone to error. Importantly, it is impossible to relate the body surface information to a specific location in the heart since the electric potential at any body surface point reflects the integrated electrical activity of the entire heart. It is clear, therefore, that ideally the cardiologist should have access to information measured directly from the heart. Unfortunately, obtaining such information requires open-heart surgery and the placement of an electrode “sock” over the heart surface.

Similar in concept to CT or MRI, Electrocardiographic Imaging (ECGI) uses mathematical methods to noninvasively reconstruct the electrical activity of the heart from the total body surface ECG. The result is a close approximation of the electrical measurements that would have been obtained by electrodes in direct contact with the heart, but without the need to approach the heart physically.

The development of ECGI in our laboratory started with laying the foundation for the mathematical reconstruction methods and validation of the approach. The complexity of the mathematical methods and the sensitivity of the reconstruction procedure to error require careful validation and evaluation of the noninvasively reconstructed heart potentials, ideally through comparison with those measured directly from the heart surface. For validation purposes, we have used information collected in collaboration with Dr. Bruno Taccardi at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. Data were collected from a torso-shaped tank (molded from the torso of a 10 year old boy) containing a dog’s heart suspended in the correct human anatomical position and maintained by a blood supply from another dog. 400 body-surface electrodes and 200 heart-surface electrodes are used to simultaneously measure the total body surface ECG (the BSPM) and the heart-surface electrical activity, respectively. The BSPM provides the data for the noninvasive reconstruction of heart potentials, using our ECGI methodology. The information measured by the heart-surface electrodes provides a “gold-standard” for comparison and evaluation of the noninvasive ECGI reconstruction.

Using torso-tank data, we have demonstrated that single or multiple sites of arrhythmogenic activity in the heart (known as arrhythmogenic or ectopic foci) can be noninvasively reconstructed and located with an accuracy of 8 millimeters or better. The noninvasively reconstructed electric signals on the heart surface (electrograms) closely resemble their directly measured counterparts, and the entire sequence of cardiac activation is reconstructed by ECGI with high accuracy. With this level of accuracy and resolution, ECGI can be used to diagnose rhythm disorders of the heart, help surgeons plan antiarrhythmic heart surgery and guide them to the affected sites, or, even better, help in guiding catheters to ablate the arrhythmogenic foci without the need for surgery. More recently, we demonstrated the ability of ECGI to image prolongation of repolarization in the heart as occurs in the LQT syndrome, to capture the reentry circuit during a ventricular arrhythmia, and to image abnormal electrical substrates associated with myocardial infarction [Circulation, 2000]. Our first report on ECGI application in humans [Nature Medicine, 2004] includes examples of imaging normal activation and repolarization, conduction abnormality, abnormal ventricular activation sequences, and the reentry circuit in a patient with chronic atrial flutter.

The Future – Mechanism Based Therapy

Prediction is very difficult, especially about the future

— Niels Bohr

Using novel and ingenious approaches to research, biomedical scientists are providing, at a dazzling pace, new seminal information on the mechanisms of cardiac rhythm disorders. Molecular genetic technology has made it possible to identify genes that, when mutated, alter the molecular structure of specific ion-channels or gap-junctions. Molecular biology techniques, together with sensitive methods for measuring currents through individual ion channels, can be used to relate such structural alterations to abnormal channel or gap-junction function (the LQT syndrome serves as an example, where specific gene mutations were identified and related to altered structure and function of sodium or potassium ion channels). With the aid of mathematical models, abnormal channels or defective gap-junctions can be introduced into models of the whole-cell and multicellular tissue to simulate and predict their arrhythmogenic consequences. Important insights into the multicellular mechanisms of cardiac arrhythmias can also be provided by advanced, high resolution mapping techniques. Optical mapping uses voltage sensitive dyes and photodiode arrays to simultaneously image action potentials from many sites. Electrical mapping uses a large number of electrodes to map the global sequence of action potential propagation in the heart. Based on synthesis of the information gathered by these different approaches, a more coherent picture of cardiac arrhythmias is beginning to emerge.

The ability to link a clinical rhythm disorder to its genetic basis and to structure-function alterations in a specific ion channel opens the exciting possibility of targeting therapy specifically toward the abnormal channel. Mathematical models could be used to simulate and examine the effects of possible therapeutic interventions. Such interventions could include drugs or genetic modifications designed to neutralize or correct the abnormal arrhythmogenic function of defective ion channels or gap junctions. For example, in the type of LQT syndrome caused by sodium chancel mutation, the defective channels reopen during the action potential plateau, causing its abnormal prolongation. Gene therapy could be aimed at modifying the channel molecular structure, thereby correcting its abnormal functioning. Alternatively, a drug can be designed to bind to the channel protein and prevent the channel from reopening.

A therapeutic approach with such high degree of specificity will require noninvasive diagnostic tools that are both very sensitive and highly specific imaging modalities for cardiac electrical function, such as ECGI, could provide a specific, mechanism-based diagnosis of rhythm disorders. Such methods could also be used to screen and identify patients at high risk of sudden death before they experience a life-threatening arrhythmic event. Early identification and diagnosis could then be the basis for preventive intervention using genetic or drug therapy as discussed above, or alternatively a protective implanted device (e.g., pacemaker or defibrillator).

The future of genetic and molecular medicine is exciting and major strides in this direction have already been made. To some it might sound as science fiction (or medicine fiction..). I would like to end this article with this quote from Through the Looking Glass by Lewis Carroll:

Alice laughed, ‘There’s no use trying.’ she said; ‘one cannot believe impossible things.’ ‘I daresay you haven’t had much practice,’ said the queen. ‘When I was your age, I always did it for half-an-hour a day. Why, sometimes I’ve believed in as many as six impossible things before breakfast.’